Outside the Yuengling Center on the first day of March, the palm trees are still and partly cloudy skies are barely partly cloudy. Inside, the mood matches the moment. The South Florida men’s basketball team is smiling and breezy before what’s to be a light practice. A final home game, and the Senior Day celebration that comes with it, awaits the following afternoon. The season has not been what anyone expected, largely because the person everyone wants to be here isn’t. But this is a morning to stare at the bright side.

“It’s a great day! It’s a great day!” hollers guard Brandon Stroud, one of the trio of seniors who will be feted in about 24 hours, easily overcoming the music blasting from a sideline speaker.

Three nights earlier, Stroud collapsed into a staff member’s arms, sobbing, during starting lineup introductions at Temple. He didn’t countenance Amir Abdur-Rahim’s death for months. Not really. He banished the reality from his mind, even as he bought Girl Scout cookies from his coach’s daughters or raced trucks with his coach’s son. Then the wall came down and the rockslide of grief followed. Stroud couldn’t stand. He couldn’t play. He couldn’t think about anything, except what he lost.

“I just want to go at it one more time,” Stroud says, sitting in a quiet media room after practice. “Yell at him, he yells at me. That’s all I think about most of the days.”

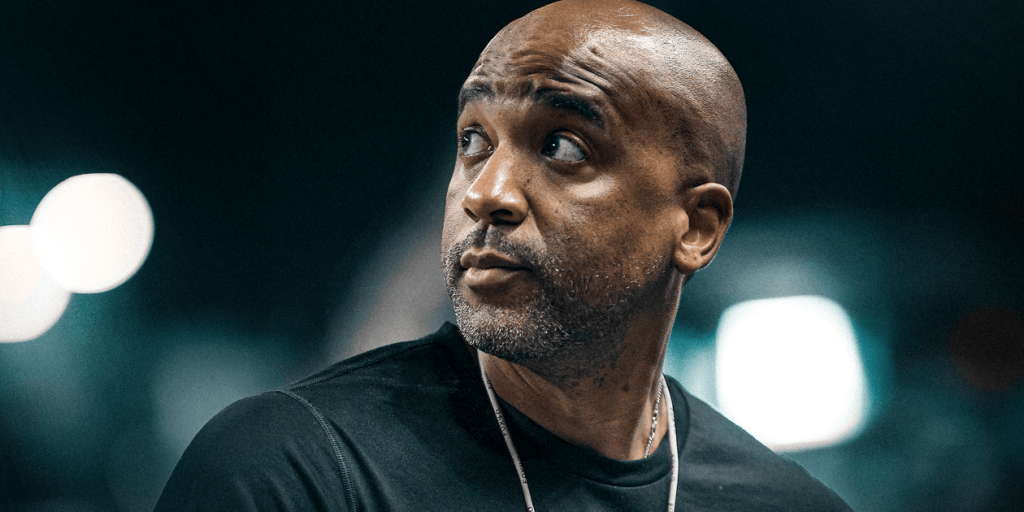

On Oct. 24, just 11 days before a season-opening game against Florida, Amir Abdur-Rahim checked into a Tampa-area hospital for an undisclosed medical procedure and died of complications that arose. The news leveled everything in sight. At 43, Abdur-Rahim was one of college hoops’ skyrocketing coaching stars, turning Kennesaw State from a one-win punchline into an NCAA Tournament team and then leading South Florida to a league championship and its first-ever appearance in the Associated Press Top 25 poll. “We knew where he was going, man,” is how one of his close friends, Missouri coach Dennis Gates, puts it. Suddenly, that incandescence was simply gone.

As coaches from across the country this week make their annual migration to the Final Four, fully grasping the empty space in their midst requires measuring beyond the sidelines.

The calls in times of need. The cooking. The grilling. The voicemails reminding peers he was going to stay on them to succeed. The weddings. The Valentine’s Day shopping trips to address what he deemed to be poor gift ideas. The free donuts and coffee, for whomever, just because. The “Love Wins” speech. Everyone who knew Amir Abdur-Rahim sees the hollow where he’s supposed to be. The only thing to do is fill it with the story of who he was.

“I experienced him every day,” says Arianne Abdur-Rahim, his wife of 12 years, her voice catching. “Which makes the void that much bigger. Because he was really special. And I love that the world sees that.”

The argument was bad enough that Steve Prohm worried his relationship was over. And he was crushed. A fellow Murray State assistant noticed how distraught he looked, inquired as to why and got the full story. Unbeknownst to Prohm, Amir Abdur-Rahim later logged on to Facebook and sent a long message to Katie Ross. He assured her that Prohm thought the world of her, declared her boyfriend to be one of the best people Abdur-Rahim knew and begged her to give Prohm another chance.

Katie Ross is now Katie Prohm. And Amir Abdur-Rahim was a groomsman in the wedding.

“He led with the heart,” Steve Prohm says now.

The memories and anecdotes are seemingly endless, tributaries from the same deep pool. Abdur-Rahim was not simply the peer who built a Rolodex over stops at Murray State, Georgia Tech, Charleston, Texas A&M, Georgia, Kennesaw State and, ultimately, South Florida. He was the friend who many in the profession turned to as a sounding board for whatever was going on in their lives. “When he met you one time,” Indiana assistant coach Yasir Rosemond says, “it was like he knew you for 10 to 15 years.” Some talked to him daily. Others a couple times a week. His bandwidth for the people in his life made it seem like he’d cheated the clock and added a few more hours to each day.

“I would tell the dude all the time, ‘Man, I feel like you work for AT&T,’” says Ben Fletcher, who served as South Florida’s interim coach this season, “because every time I see you, you’re on the phone.”

“It’s amazing,” Kentucky assistant coach Alvin Brooks III says, “that he made all of us feel like brothers.”

He had built-in expertise there. Abdur-Rahim was one of 13 siblings growing up in Marietta, Ga., and one of six brothers who played college basketball. The oldest cast a pretty wide competitive shadow — Shareef Abdur-Rahim starred for one year at California, logged 13 seasons in the NBA and currently serves as president of the G-League — but which built the most enduring legacy was an open question.

Amir couldn’t have been 10 years old, Shareef says, when the two of them were at a community center and Amir spotted a couple other kids horsing around near a large, thick slab of plywood leaning against a wall. The warnings from adults to stay away weren’t working. So Amir walked over to pull the two kids back for their protection. Seconds later, the plywood tipped over. The other children escaped unscathed while the slat landed on Amir Abdur-Rahim’s foot and broke it. “I hadn’t thought about that in forever,” Shareef says. “But it’s all those types of things. How courageous he was. How much he cared about people.”

Arianne Abdur-Rahim regularly told her husband he was the better parent, and not just because she saw her kids get a bit too delighted when it was Dad’s turn to make dinner. She concedes it’s a strange conclusion to make about someone invested in an overly stressful, all-consuming profession that severely limits time at home.

But one of Abdur-Rahim’s mentors, former Texas A&M coach Billy Kennedy, always preached to his staff to make time for family. So, when Amir Abdur-Rahim was with his kids, he was with them, be it reading with Laila, the oldest, letting middle-kid and “personality twin” Lana hover over him everywhere or playing on the mini-hoop planted in the middle of the living room with his son, Aydin. “Amir loved being a dad,” Arianne says. “I don’t think there was any job he loved more.”

Gates often called Abdur-Rahim in the mornings, and if Abdur-Rahim was driving his kids to school — which he did every day — he’d tell Gates he’d call him back. “He wanted to be present,” Gates says. “That was his thing.”

It’s only semi-remarkable — lots of busy parents are also very good parents — until you consider how diligent Abdur-Rahim was about making it everyone else’s thing, too.

There was saving Prohm’s marriage before it was a marriage. There was actually saving Jordan Mincy’s marriage with his counsel, according to Mincy. “If it weren’t for him and his guidance and being there, bro, I would have been divorced,” the Jacksonville coach says now. There was lending an ear to Brooks, who felt like he wasn’t around enough for his wife and sons in the 2023-24 season at Baylor, and hitting him with a challenge in return: Treat your family like you treat recruits and your players, because whenever God decides for you to leave Waco, there’s only three other people that’s going to go wherever you go.

There was the time at Kennesaw State when, two days before a game at Liberty that would determine first place in the league, Abdur-Rahim and assistant coach Pershin Williams stopped game-planning to make an impromptu trip to the mall. Abdur-Rahim had asked Williams what the assistant was buying his wife for Valentine’s Day, and determined it was not good enough. (Abdur-Rahim did the same with Williams’ younger brother, Donovan, who was on staff at South Florida.)

Last summer, Abdur-Rahim investigated how much it would cost to bring significant others on South Florida’s preseason tour in Spain, motivated in large part by a desire to give assistant coach Ben Fletcher the opportunity to propose to his girlfriend. Upon landing, Abdur-Rahim pressed Fletcher for the plan. I don’t even have the ring yet, Fletcher protested. (He did, eventually, propose.)

No wonder Marquette assistant coach Neill Berry notes that how many weddings Abdur-Rahim attended is not the incredible part; it’s how many weddings Abdur-Rahim was in. “I actually changed my wife’s name in my phone because he made me feel bad,” says Kansas State assistant Ulric Maligi, who worked at Texas A&M with Abdur-Rahim. “He had Ari as ‘My Beautiful Wife’ in his phone. I was like, man, I can’t let my wife see that.”

“Love Wins” became Abdur-Rahim’s mantra, after he addressed his Kennesaw State team after its 2024 NCAA Tournament loss with only those two words written on the whiteboard behind him. The phrase was printed on T-shirts distributed and worn at South Florida home games during the 2024-25 season. It was fused onto the spine of his teams’ success.

Left everything out there.#BONE | #HootyHoo 🦉🏀 pic.twitter.com/FsJNgsZ5tz

— Kennesaw State MBB (@KSUOWLSMBB) March 19, 2023

On his recruiting visit to Kennesaw State, Stroud walked into an elevator with Abdur-Rahim and found himself in the midst of a wrestling match with the head coach of a Division I basketball program. “Nothing else about Kennesaw made me commit to Kennesaw but that,” Stroud says now.

Last season, after a poor practice and harsh words from the head coach, Jayden Reid heard a knock on his door at 7 p.m. In came Amir Abdur-Rahim. First, he pummeled Reid with pillows. Then he explained why he was pushing the then-freshman so hard. “I don’t feel like any other head coach is doing that,” Reid says.

Before a game against Florida State in November 2023, with South Florida on a three-game losing streak, Abdur-Rahim ended a film session by telling each player in the room what he did well and why he loved them.

“Dudes left out of there with tears,” Fletcher says.

The Bulls won by 16 the next night.

“He touched a lot of lives, man, and it was all genuine,” says Tom Crean, who hired Abdur-Rahim as an assistant at Georgia. “That’s why it worked.”

Still, the corollary to his affection was insistence. Kasean Pryor was the third-leading scorer for that breakthrough 2023-24 Bulls squad, reaping a nice Name, Image and Likeness windfall in a transfer to Louisville. Last summer, Pryor saw his old coach had left him a voicemail, asking if he was going to be lazy now that he had some money in his pocket.

I’m still on your ass, Abdur-Rahim said in the voicemail. You’re my guy.

As Maligi puts it: If a player wanted to be average, he probably didn’t much like being around Amir Abdur-Rahim. There was one way forward, as defined by Abdur-Rahim, and the guardrails never shifted. “The Donkey” is what current Xavier assistant Isaac Chew called Abdur-Rahim during their time together at Murray State, owing to Abdur-Rahim’s refusal to budge from what he believed.

“He was stubborn with a cause,” Arianne Abdur-Rahim says.

It was how he got what he wanted, at least on the basketball floor.

It was, in the end, how Amir Abdur-Rahim’s teams made indelible history in a short time.

William Abdur-Rahim played college football at Fort Valley State University. He understood how grueling the sport could be, was happy to play catch with his sons and also expressly forbade them from playing the sport. His kids begged. He did not relent. So, one year in middle school, his son Amir signed himself up. He sneaked out to practice. He hid his uniform. His parents only discovered the ploy when the hospital called to inform them Amir had broken his ankle during a game.

“Think about that,” Shareef Abdur-Rahim says with a laugh. “In a lot of ways, to do what he did at Kennesaw State, you have to have some of that in you.”

Amir Abdur-Rahim landed his first head coaching job in 2019, at a school that hadn’t enjoyed a winning men’s basketball season in its first 14 years of competition at the Division I level. On game days, he and Williams walked around campus and handed out pamphlets to students, to clue them in on that night’s proceedings at the KSU Convocation Center. In his first season, the Owls went 1-28. But after his team’s second meeting with Kennesaw State, Liberty coach Ritchie McKay pulled Abdur-Rahim aside and repeated the advice McKay and Tony Bennett had followed while building up Virginia men’s hoops: Get guys you can lose with first.

The next two seasons were better — 5-19 and 13-18, respectively — and Abdur-Rahim remained steadfast. He believed he had the right core of players. The 2022-23 season proved it: The Owls were picked sixth in the Atlantic Sun preseason polls but won the league and hosted the conference tournament. In the title game, they met McKay’s Liberty Flames.

That day, as they’d done every game day, Williams and Abdur-Rahim walked campus handing out their pamphlets. The building was packed. A Terrell Burden free throw with 0.7 seconds left sent Kennesaw State to its first-ever NCAA Tournament. The students rushed the floor, consuming the Owls and blocking them from the postgame handshake line. (Their coach had his players do it later.) But Abdur-Rahim was there to shake McKay’s hand, and McKay was reminded of a line Liberty’s pastor once shared: “Love is wanting for someone else what you would want for yourself.”

“I just thought, man, I’m really proud of you,” McKay says. “If this couldn’t be us, I’m glad it’s you.”

Abdur-Rahim officially became South Florida’s coach on March 29, 2023, but not before expressing his angst about what would happen to his players and staff to Shareef. And not before a phone call with Stroud in which Abdur-Rahim cried through an explanation about how he could help more people in a bigger way by making the move.

But, once in Tampa, Abdur-Rahim chased down a community instead of waiting for one to come to him. He handed out donuts to students at the library. He bought coffee for complete strangers. “I would call him and he’d be like, ‘Hey, babe, I’m at Starbucks right now, I got to call you back, there’s like a line, like a hundred people,” Arianne Abdur-Rahim says. Within a year, the program had won a regular-season conference championship that later would be memorialized with only the fifth banner in the Yuengling Center to recognize any sort of men’s basketball achievement, and the first since 2012.

It was raised to the rafters on Nov. 12. Nineteen days after the sky fell.

The text came from Joi Williams, South Florida’s chief of staff, while Fletcher was on the phone with his fiancee: Are you at the hospital? Fletcher responded with two question marks.

“We knew nothing,” Fletcher says. “Yeah. Nothing.”

On Oct. 24, South Florida gathered the players into a film room that was more crowded than usual with school officials. “So I knew something was off,” forward Quincy Ademokoya says. Administrators confirmed that their head coach was dead. The team’s immediate denial was undermined by the tears on everyone else’s cheeks. “You think it’s not true, but it’s like, this is real life,” Reid says.

Everything stopped but kept moving ahead all at once. Fletcher became the interim head coach, awash with a guilt about getting the job that way. The team didn’t practice for three days. After traveling to Atlanta for a celebration of life event on Oct. 27, the players collectively decided to return to work.

It was one of the best practices South Florida had all season.

“You could feel Coach Amir’s energy in the gym,” Reid says. “The intensity, the energy, the talk. And I feel like that’s when we kind of understood – he’s not here. We have to carry on the legacy. It’s on us.”

South Florida coach Amir Abdur-Rahim is remembered before a game against Florida at VyStar Veterans Memorial Arena on Nov. 4, 2024, in Jacksonville, Fla. (James Gilbert / Getty Images)

It’s 10 minutes past noon on Senior Day, and Arianne Abdur-Rahim sits down at last.

For a solid half-hour, at least, she has been moving up and down and around the Yuengling Center in a green sleeved dress and black heels, doing a job she is both happy and heartbroken to do. From the floor, she watches a video honoring South Florida’s seniors with athletic director Michael Kelly on her right and Fletcher on her left. She walks to midcourt, delivering hugs to the seniors and their families and smiling for the pictures. She makes her way up the stairs to an open-air private seating area, stopping to say hello to familiar faces along the way. She then entertains more visitors and delivers more hugs once in the box. She chats with Kelly’s wife and makes sure her daughters are fed. Not until the game against Florida Atlantic reaches the first media timeout does she get off her feet.

She met Amir at a Fourth of July party in Atlanta. One of her law school friends knew the person throwing the bash, so they drove up from Florida. Amir Abdur-Rahim was there because he knew the host, too. Since kindergarten, actually. Thus one of his lifelong connections begat another: Arianne and Amir started talking at that party and never stopped. She didn’t have any clue what a college basketball coach did at first. Years later, she knows what she was missing.

“I learned, obviously, what this life is about,” Arianne says. “And I learned the beauty in it all. And I learned the passion that he has for this industry. And so to be able to do Senior Day on behalf of him, it was my honor to be there.

“Obviously, for every emotion, there’s the opposite emotion in this, right? Because I wish he was there. I wish he could have done that. But as I grow in this moment of acceptance, I have to take on those things. Because I know it’s what he wanted.”

The sadness has come in different ways and at different times for everyone. What comes next is almost always the same: Looking for someone who’s not there. “I have an absence,” says Gates, who carries the booklet from the celebration of life with him. That is a forever burden. But then you talk to one person about Amir Abdur-Rahim, and that person tells you someone else you have to call. Then that call leads to another. And another. And soon it’s a chain of light illuminating the way out.

“He was the guy that had that glow,” says Darby Rich, Texas A&M’s strength and conditioning coach during Abdur-Rahim’s time there. “It made you want to be better, to do better. Because you saw the impact he was having on others.”

It’s a story Shareef Abdur-Rahim has told before, but he’s more than willing to retell it: He flew into Atlanta for reasons he can’t remember following the 2023-24 college basketball season, after the revival at Kennesaw State had captured everyone’s attention. He took the train to the rental car center, approached a clerk and handed over his driver’s license.

“Abdur-Rahim?” she asked.

A former high school superstar from the area with a career of more than 800 NBA games behind him said, yeah, Abdur-Rahim.

“Like the coach?” she replied.

It hit like a gale, after so many years of his talent and his accomplishments casting a shadow over his siblings. It felt, he says, very cool.

That’s my brother, Shareef told her.

“No,” the clerk replied, “you’re his brother.”

Shareef Abdur-Rahim smiled. He didn’t correct her.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; photos: Jared C. Tilton / Getty Images)