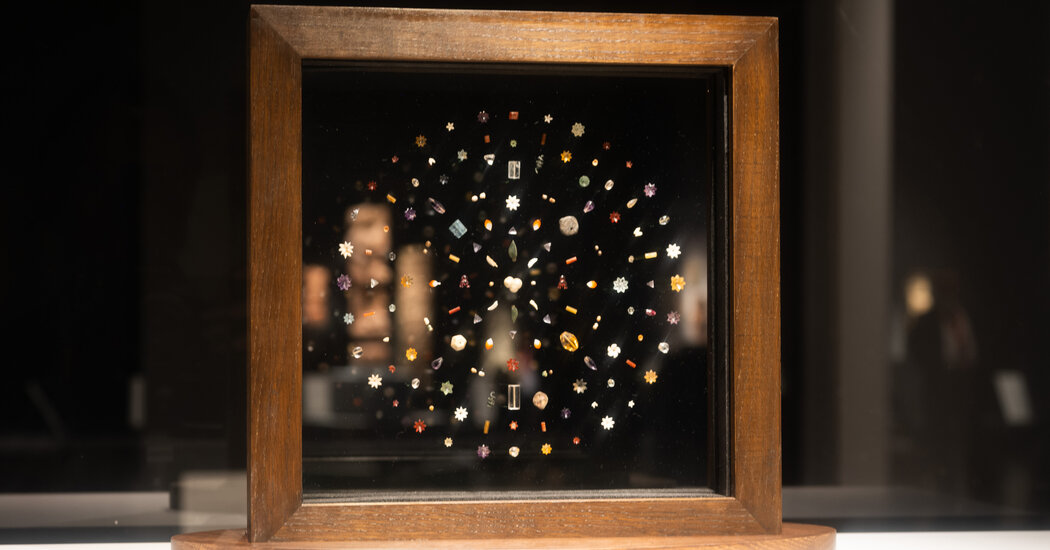

The jewels are delicate, some just millimeters in length, arranged in intricate patterns of circles and lines. Taken from British-occupied India in 1898, the jewels were discovered alongside bone and ash, said to be the remains of Buddha. The collection is perhaps one of the holiest relics in contemporary religion.

Now, it is up for sale, igniting a legal battle between the government of India and Sotheby’s, the international auction house set to sell the religious treasures in an auction. The artifacts are being sold on behalf of the English descendants of the explorer who dug them up more than 120 years ago.

On Monday, the Indian Ministry of Culture issued a legal order, saying the relics should be returned to India for “preservation and religious veneration.” Sotheby’s initially defended the sale but later announced that it would postpone the auction, originally scheduled to take place on Wednesday in Hong Kong. “This will allow for discussions between the parties,” it said in a statement.

The sale cuts to the heart of an uncomfortable question that has roiled post-imperial nations: How should priceless relics plundered generations ago from once-occupied territories be handled?

“We’re in this movement that’s long overdue, to rethink the status of culturally significant artwork,” said Ashley Thompson, a professor of Southeast Asian art at the University of London. “Who do they belong to? What are they worth? Can they even be considered as commodities?”

A host of countries have wrestled with such questions in recent years. Some American institutions have slowly begun returning relics to Indigenous tribes. Dutch museums have returned colonial-era artifacts to countries like Nigeria and Sri Lanka. Across Britain, museums have gradually been repatriating looted artifacts, including some related to Buddhist burial traditions.

But the Buddha-related jewels for sale this week, known as the Piprahwa gems, have their own unique complications. They are not held by a museum or a state, but rather the family of William Claxton Peppé, the English explorer who excavated the holy burial ground in 1898.

That discrepancy presents an ethical conundrum, said Naman Ahuja, an art history professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi who studies museum administration and repatriation.

“Noting the ethics of the situation and public sentiment, the British state did the right thing and returned relics in 1952,” Mr. Ahuja said, referring to other repatriated Buddhist items that had been returned by England. “But individuals who occupied a colonial position were not held accountable.”

According to a description of the jewels on the Sotheby’s website, Mr. Peppé discovered the artifacts while excavating land in Piprahwa, a village in northern India. Unearthed from a sacred burial ground known as a stupa, the collection was found with bone and ash remains long considered to be those of Buddha, who was believed to be buried in the area.

At the time, Mr. Peppé turned over much of his find to the British state, donating other parts to scholars and museums, including the Indian Museum in Kolkata. But he was permitted to keep some of the relics, which have been passed down for generations in his family.

Chris Peppé, one of three descendants who now possess the relics, told the BBC that the family had explored donating the collection to various Buddhist stakeholders, but that doing so would have presented unspecified problems. The auction was the “fairest and most transparent way to transfer these relics to Buddhists,” Mr. Peppé said.

In its order demanding the sale be stopped which was posted on Instagram,

India’s Ministry of Culture issued contends that the Buddhist relics should be offered back to the Indian government rather than auctioned. The Peppé family, it said, “lacks the authority to sell these objects.”

Tiffany May contributed reporting from Hong Kong.