SOUTH BEND, Ind. — Through warmups and the game, the cell phone sat on the team’s bench.

In the small gym in Brookville, N.Y., Long Island, no opponent could match Kate Koval that February night. Her coach yelled to her, calling the plays, and Koval instinctively reacted. Her body was on the court, but her mind was elsewhere.

She repeatedly glanced at the bench to see if the phone had lit up or vibrated. She heard all the sounds of the gym — shoes squeaking, buzzers, whistles, fans — but all she focused on was a ring from the sideline. A timeout from her coach. A voice on the other end of the call.

Before the game, her coach, Christina Raiti, had asked the opposing coach and head referee to make an exception to the rules and allow the phone on the sideline. They all agreed and said she could call a timeout — no matter which team had possession — if it rang.

They all hoped it would. But it remained on the bench. Silent.

That morning, Koval had woken around 5 and received a call from her mother, Natalia.

She and Kate’s father were OK, her mom emphasized as she rushed around the apartment, preparing to evacuate Kyiv, Ukraine. They would call later when they could.

Koval’s parents lived near the city center, not far from the main government buildings. Hours before, at dawn on Feb. 24, 2022, Russia had invaded Ukraine. Explosions had been reported across the country, from Kyiv to Chernihiv to Odesa.

Leading up to the invasion, Koval assured her friends in New York, where she had lived for the past five months pursuing her basketball career, that the mounting threats weren’t unusual. Since late 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin had been massing Russian troops on the Ukrainian border. Russia had long held a presence in Ukraine.

But this was different.

When her parents had called that morning, her dad, Oleksandr, said that once they got to safety, they’d try to watch a live stream of her game that night.

She reminded herself of that throughout the day as images of bombed Ukrainian cities and casualty counts — military and civilian — rolled in. Surely, Koval thought, if her dad had basketball on his mind, things couldn’t be that bad.

Throughout the day, she called and texted her parents, but her messages were left unanswered — or maybe they hadn’t even gone through, she thought. When she arrived at the gym, almost 12 hours had passed since Koval had heard from her parents. When Raiti suggested canceling the game, Koval was incredulous.

She couldn’t stomach the idea that her parents, possibly sitting in a bomb shelter while their country was under attack, wouldn’t be able to see her. She didn’t know if they were OK, but if they could check her game, she wanted them to see that she was.

So, Koval played. And the phone sat on the bench throughout the game, waiting for a call that didn’t come.

In 2021, when Koval was 15 and living in Kyiv, she was reaching a limit. She had competed with Ukraine’s youth national teams since she was 12, playing up two to three years, and with a club team that traveled internationally.

Oleksandr had been the one who helped push her sports dreams. As a child, she split her time between ballet and basketball, but when adolescence hit, she chose the hardwood. Oleksandr read up on nutrition and weight training to help his daughter excel. He helped with her mental approach, too. “He could’ve been a psychologist if he wanted,” Koval said.

She understood her best path to the WNBA went through a U.S. college. At 6 feet 2 (and still growing), she had maximized her development in Ukraine. The Kovals began researching schools where she could get a jump-start on the American basketball experience.

In four years, she’d become a key player on a Notre Dame team eyeing a national title, but in the spring of 2021, she was just an unknown entity in a country un-renowned for producing women’s basketball talent.

A scout had sent video of Koval to Raiti, the Long Island Lutheran High (LuHi) coach. The program was solid in the Northeast, but Raiti sought more talent to make it a national power. Koval, Raiti knew, could change LuHi’s trajectory.

On a video call Raiti had arranged with Koval and her parents, Oleksandr peppered Raiti with questions about LuHi’s academics and his daughter’s potential living arrangements. Oleksandr and Natalia had advanced degrees and supported their daughter’s WNBA dream, but they also wanted to ensure it didn’t impede her pursuit of a neuroscience major.

Raiti assured them Koval would have the best of both worlds at LuHi.

By August 2021, Koval was on a plane to JFK. With her mom and grandma helping, she moved in with her host mom, Islande Blaise, in Queens. Koval and her family met Raiti for dinner in the city one night. Koval said little, but as they left the restaurant, she pulled Raiti aside and said: “I’m ready for this. They’re the ones who are nervous,” motioning to her mom and grandma.

Koval’s transition to New York was rocky. Her classmates and teachers spoke too quickly (“I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, my textbook English is not helping,” Koval said), and like any new kid, making friends was daunting. In basketball, the American game proved faster and more physical. The coaches pushed her to her limits in practice.

“She was quiet at first, very quiet, just taking it all in,” Raiti said. “But she really started to let her personality shine through a bit.”

By age 15, Kate Koval had her sights set on playing basketball for a U.S. college. (Cameron Browne / NBAE via Getty Images)

When Koval thinks back to before the war, what she remembers most is her grandmother’s house outside of Kyiv. The yellow home, the pool in the backyard, the gate that opens to the forest behind the house. She thinks of summers walking the dirt paths between the pines and poplars and of winters by the fire, eating her grandmother’s borscht. She recalls Christmases when she and her two brothers would play with their new toys in the basement as the adults played cards and drank upstairs.

Though the rest of the house was immaculately decorated for the holidays, the basement was bare, save for an undecorated Christmas tree in the corner. When she was little, Koval would steal ornaments off the tree upstairs so the basement could be festive, too.

Koval’s parents grew up in Ukraine. Their parents were born in Ukraine. Their parents’ parents were born in Ukraine. Through generations, family holidays have always been an important time for everyone to be together.

When the Koval kids’ playing would devolve into arguments, Oleksandr — the family disciplinarian — would go down to the basement and tell them to solve their issues on their own. But, Koval said, his discipline always came with a deeper meaning and message. It wasn’t about the fight; it was about the resolution. Mostly, it was about family.

“He would always say, ‘When me and your mom are gone, you guys are the only thing you will have,’” Koval said. “‘You guys can fight. You guys can not talk for weeks, but this sibling blood is something that you will not be able to replace. Your friends will come and go, but you know you will always have your two brothers no matter what.’”

He would go back upstairs, and the three kids would hash it out.

On the day of her game at LuHi, when she couldn’t get ahold of her parents, Koval found herself thinking back to those holidays. Her family. The food. The sound of a house full of laughter and love.

And she thought about the basement. Throughout her life, it had been a playroom, an office, a storage room. But it served a vital purpose as well. In the event of air strikes, the concrete basement could act as a bomb shelter, too.

When the call finally came, it was from Natalia. Koval was back in Queens by then, waiting in her new home, scrolling her phone for updates on her old city.

Her parents had safely evacuated and fled to Kate’s grandma’s house. They had huddled in the familiar basement, but things were quiet for now. It was OK, Natalia assured her daughter. It was morning in Kyiv, and — as the Kovals rightly assumed — nighttime would be the most dangerous time in this war.

“Kate and her brothers were nervous, and they were shocked. But you know, I think that they were afraid more than we were,” Natalia said. “When you are already in the middle of these events, it is not so scary as from (the) outside.”

Natalia and Oleksandr told Kate they were most grateful they didn’t need to worry about the safety of their children, who were all living in the U.S.

In the coming days, Blaise and Raiti did their best to shelter Koval from the news, but images of Ukraine were impossible to avoid. They were in newspapers and all over social media. Koval saw reporters in front of familiar buildings and parks. In the first week of the war, the gym where she learned to play basketball was bombed. Days later, Kate received word that her friend Nastia was fatally shot while trying to flee to Slovakia.

“You will not feel the pain of it until you really lose somebody who you’ve known to the war,” Koval said. “That definitely made it more real for me.”

From 5,000 miles away, every update felt like a shock wave through her body. As she went through her daily life, attending classes and playing basketball, it often manifested as guilt.

“I was just blaming myself,” Koval said. “Why am I here and my family is over there? Why am I safe and my family has to go through all that?”

The trip from Koval’s home in Queens to her school in Long Island took roughly two hours, sometimes more.

She’d listen to music, do homework and call her parents in Kyiv. They wanted to know how she was acclimating, how she was eating, how basketball was going. Koval wanted to know what her parents had been up to, how her grandparents (adamant about staying in Ukraine) were doing, how her cat was faring without her.

Before the war, these conversations were relaxed. Afterward, the tone changed. She’d count the number of rings until they picked up.

Shortly after the Russian invasion, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy decreed men ages 18 to 60 could not leave the country. That included Oleksandr, then 48. After high school, he had attended Ukraine’s top military school and became an air-force engineer. Following retirement from the military, he earned a law degree before settling into life as a businessman. Since then, he had been running the family business, a medical testing company, where Koval’s mother worked as an accountant.

Koval understood that her dad couldn’t leave the country, that he was honored to enlist in the war efforts and return to his roots in aviation engineering. But she initially begged him to find a way out.

“He told her that every man should protect his home, his land, his country, and this is normal, and this is obvious,” Natalia said. “As she is Ukrainian, she understood.”

As the war carried on in Ukraine, and in what felt like a blessing to Koval’s parents, their daughter’s college recruitment heated up. It gave them a lot to talk about in those daily calls right around Oleksandr’s lunch breaks. What schools was she hearing from? What did she think of the coaches? How were the academics?

In her second year at LuHi, the program was becoming a national power. Nearly every power conference school wanted Koval — now a 6-5 forward and top-10 recruit, considered the best post in her class.

As coaches called, Koval made clear that she needed a place to call home, a team that felt like a family. Every recruit says this, but those words meant something different to Koval. Her family had been torn apart, and she wasn’t sure she would ever see the apartment she called “home” again.

“I don’t have my family by my side all the time, so I need to be in a place that feels like home,” Koval said. “I didn’t want to go to a huge school when you’re just gonna be a number.”

That summer, after playing in Hungary with the U18 Ukrainian 3×3 team, she and her brother bused to Kyiv to visit their dad. Since the war, she had seen him only once, when he traveled on a short-term permit to celebrate Christmas with the family in Canada, where Natalia now lived on a visa to be closer to her children in the U.S.

Nearly two years had passed since Koval had been to Ukraine, more than a year since the war began. Most of her friends had left.

Air-raid sirens blared through the city nearly nightly. She hunkered in bomb shelters with her cousins some nights until it was safe to go home. During the day, life seemed … normal. She enjoyed coffee in the city, walked the streets with her dad and brother and played with her cat.

When Koval returned to New York, she reflected on the limited time she recently had with family. It clarified what she wanted most in a college.

Less than two months after visiting Ukraine, Koval chose Notre Dame. In an emotional ceremony at LuHi, she thanked her family, her coaches, her teammates and the community. She then stood and unbuttoned her varsity jacket to reveal a Notre Dame sweatshirt.

“It felt like home,” she said.

Koval couldn’t sleep. Her dad was on a flight to South Bend. She had planned a proper American college weekend: a campus tour, a Fighting Irish football game, tailgating, family meals. Notre Dame basketball coach Niele Ivey called it “Oleksandr’s official visit.”

Koval had come to campus that summer as an early enrollee. Now, the Irish were on the brink of the 2024-25 season. Oleksandr, Natalia and Natalia’s mother wanted to see Kate’s life in her new home. They cooked her favorite borscht and walked her to classes. (Oleksandr was thrilled she stuck to her neuroscience plans.)

Ivey invited them to dinner at her home. Oleksandr said little but asked Natalia to translate a message for Ivey: I see why Kate chose Notre Dame.

“She’s really found a home here in South Bend,” Ivey said. “For somebody that young to carry that much responsibility and be strong with what she does. … She never complains. I know that has to be hard for her — her family, just the last five years of her life — carrying that in her heart.”

Kate Koval, a freshman who leads No. 3 Notre Dame with 2.5 blocks per game, has found a home with the Irish. (Cal Sport Media via AP Images)

After a week, Oleksandr returned to Kyiv, where he continues to serve in the military.

Koval talks to her dad every day. He hounds her about her studies, the Irish’s season (they’re 17-2 and ranked No. 3) and her basketball progress. He looks forward to these calls as much as she does. It’s a sign of normalcy for him, too.

When he talks about his daughter, he can go on and on. “I just can’t be brief,” Oleksandr said. He’s proud she has pursued choices that require sacrifice; it means she’s preparing for the future — a similarity he notices between himself and Kate.

When their calls end, it’s hard for Kate to keep from imagining what life might be like when the war ends, when her dad can visit any time and she can return to Kyiv whenever she feels homesick.

She prays this is on the horizon.

“Having my family just like come together back to my grandma’s house for a nice Christmas dinner,” Koval said. “Every day, it’s in my prayer … just seeing families get restored and families being brought back together.

“Dads coming back to their kids and their wives.”

For now, they’ll wait for the phone to ring every day, to see each other’s name on the caller ID and hear the voice on the other end of the line.

— This story was also reported from Long Island, N.Y.

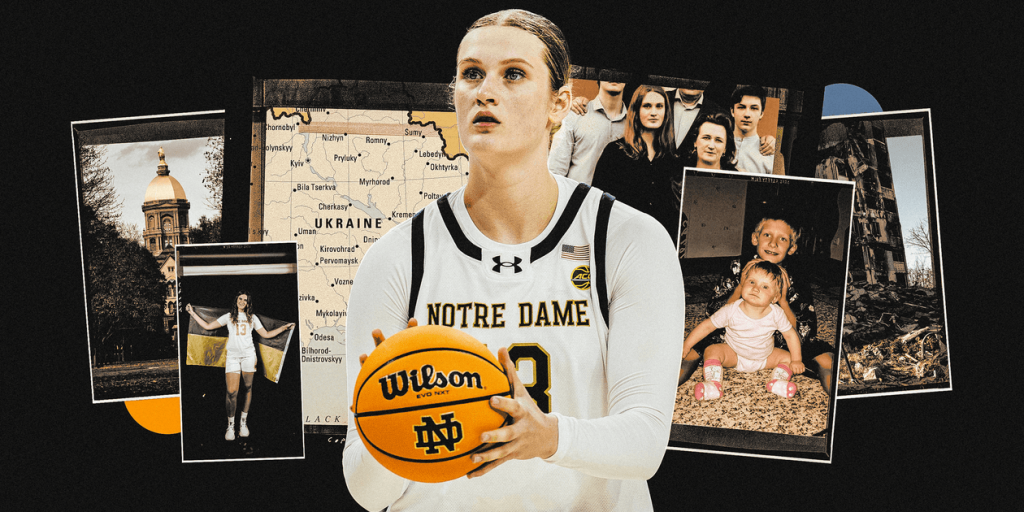

(Illustration: Demetrius Robinson / The Athletic; Photos: Courtesy of the Koval family, Cal Sport Media via AP Images, Spencer Platt / Getty Images, Joe Robbins / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images, Courtesy of Fighting Irish Media)