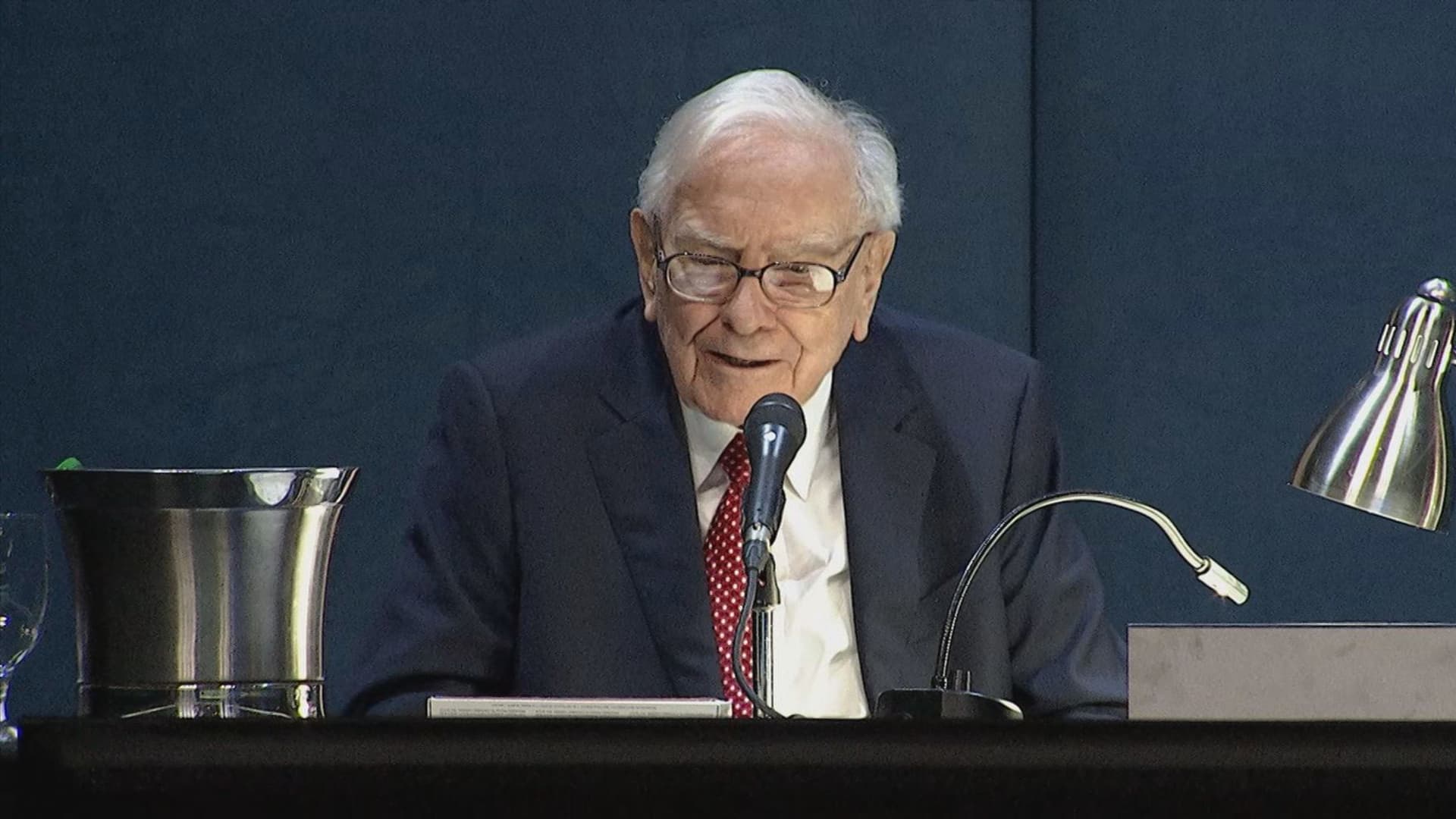

When the man who’s built the greatest fortune in history from investing alone – and whose preferred holding period is “forever” – becomes a resolute seller of two of the most widely held stocks in the world, the questions about what it means for the market and economy are inevitable. And so it is with Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway slashing its holdings in Apple and Bank of America in recent months. The Apple position has roughly been halved this year, and the selling in Bank of America last week reached nearly $8 billion since mid-July, dropping Berkshire’s stake to 10.7% of the company. Does it mean the market is too expensive even for buy-and-hold believers, that the smart money is fading this rally, that Buffett is waiting for a collapse in asset values to deploy some of Berkshire’s near-$300 billion in cash? It’s quite unlikely the proper takeaway is so simple or scary as that. Buffett himself has indicated in recent years that he doesn’t see an abundance of compelling value on offer in the public markets. And the fact that he has not made a hefty purchase of an entire company in a while, even as he constantly seeks out ways to turn cash into ownership of enduring enterprises, underscores the apparent lack of opportunities of the required size and valuation. But this in itself isn’t much of a clue about future market prospects or the macroeconomic moment. Berkshire has been a net seller of equities from its investment portfolio in each of the past seven quarters – a period in which the S & P 500 appreciated by 50%. Private investor and longtime Berkshire shareholder Ed Borgato says the Apple and Bank of America “trimming does not reflect a macro view of any kind. That would be entirely inconsistent with his sensibility and decision-making history.” Why is Buffett selling? What the sell-down in Apple and BofA probably reflect, most directly, is how large those positions became, with Apple late last year amounting to about half of the investment book. Borgato calls it an “inconvenient fact that Apple has grown to be an enormous portion of the portfolio and carries a premium valuation against a much slower growth rate.” He notes that Buffett at times has expressed some regret at not selling some of his huge Coca-Cola holdings when the stock stretched toward 60-times earnings in the late 1990s. As for Bank of America, it’s been a wildly profitable investment entered in opportunistic fashion shortly after the global financial crisis, and there is probably some rational objective at least to pare Berkshire’s stake to below the 10% threshold, above which holders need to report transactions almost immediately. It’s hard to overlook the fact that all of this is occurring as Buffett, 94, prepares the company to be run, eventually, by others. At the annual shareholder meeting in May, Buffett revealed that his chosen successor as CEO – current vice chairman Greg Abel, who came up as a utility executive and runs the non-insurance businesses – will also have final say over the investment side. This, he said, represented a shift in his thinking from a time when he thought the roles would be split. One fair inference from this is that moving capital into and out of minority stakes in public equities is likely to be a less significant pursuit of the future Berkshire Hathaway without Buffett – the childhood stock speculator and student of value investing who came to assemble his empire initially as an activist equity investor. And whatever the case, perhaps Buffett sees fit to be the one to flatten out some of the investments that had grown into outsized bets within the portfolio before any transition occurs. What you can learn from Buffett Yet even assuming it’s wrong to view these moves as a guide to market-timing, Berkshire’s situation reflects some questions that face many non-billionaire investors at the present juncture: What to do with massively appreciated mega-cap tech, how much to pay up for “quality” stocks, whether heavy cash holdings make sense as rates fall and how possibly higher tax rates should or shouldn’t dictate investment decisions now. Berkshire’s profit-taking in big positions has occurred at a time when Berkshire’s own shares have handily outperformed and have begun to look richly valued. Berkshire since the bear-market low of October 2022 has almost perfectly tracked the iShares MSCI Quality ETF (QUAL) , while outpacing the S & P 500 , a reflection on how money has flowed steadily into dominant companies with stellar balance sheets and stable profitability. BRK.B QUAL,.SPX mountain 2022-10-27 Berkshire Hathaway vs. iShares MSCI USA Quality Factor ETF vs. S & P 500 For sure, insurance stocks have also done well, and Berkshire is more an insurer than any other single thing, but the quality factor is front and center. The quality segment of the market – with plenty of representation among cash-rich, high-margin tech companies along with other high-return businesses – has served investors well over a period of uneven earnings growth and higher interest rates since 2022. Yet this market tier now trades at the high end of its historical valuation range, above an 10% premium to the S & P 500, at a time when arguably profit growth is broadening and the Fed is cutting rates into a soft-looking landing. In the process, Berkshire’s price-to-book-value ratio has climbed above 1.6, a level above which it has only spent a few months over the past 15 years. The company slowed the repurchase of its own shares to a trickle in the latest quarter, with Buffett known to be notoriously picky about what he pays to buy back Berkshire equity. And this month Ajit Jain, the vice chairman who runs the insurance division and has worked for Buffett since 1986, sold about half his personal Berkshire holdings, valued at $139 million. It’s impossible to say for sure what might’ve motivated the sale, though one could observe the stock’s valuation, Jain’s age (73) and that the Trump tax cuts are set to expire late next year unless Washington acts to preserve them. Buffett himself alluded to the prospect of higher corporate tax rates ahead when addressing sales of Apple shares early this year. The near $300 billion in cash held by Berkshire is both a buffer and a burden. Buffett has spoken of his willingness to collect close to 5%, and to act as the single largest buyer of Treasury bills, so long as he finds no ripe opportunities to acquire some rare “forever business” with it. Borgato says he believes “Buffett wants to leave a Berkshire behind that requires [fewer] future cash allocation decisions, not more.” Which would require locating high-achieving, enduring businesses willing to sell at a fair price, a tough task in a fully valued market. Of course, with the Fed in easing mode, cash yields will fall. It’s far from clear that this would change Berkshire’s willingness to part with cash or lower its hurdle rate for a new investment. Plenty of ordinary investors have found themselves satisfied to sit on idle cash given generationally high yields. I’m not a buyer of the “cash on the sidelines” case for expecting money market assets to drain into stocks. Only a third of the $6 trillion in money-market assets are held directly by retail investors. History shows only after deep bear markets have big reallocations from cash to equities occurred. Jared Woodard, Bank of America’s head of the research investment committee, showed work last week that found money-market yields need to fall below 3% or so to prompt heavy outflows, and most of that cash goes into bonds rather than stocks. Perhaps better to think of cash holdings as less a yield play than as both a cushion allowing an investor to shoulder the risk of an appreciated equity market, and as ammunition to use when compelling opportunities arise – much as Buffett does.