Key Points

- Barclays CEO says an increase in bank levy will force the sector to cut back on hiring and lending to the U.K. economy.

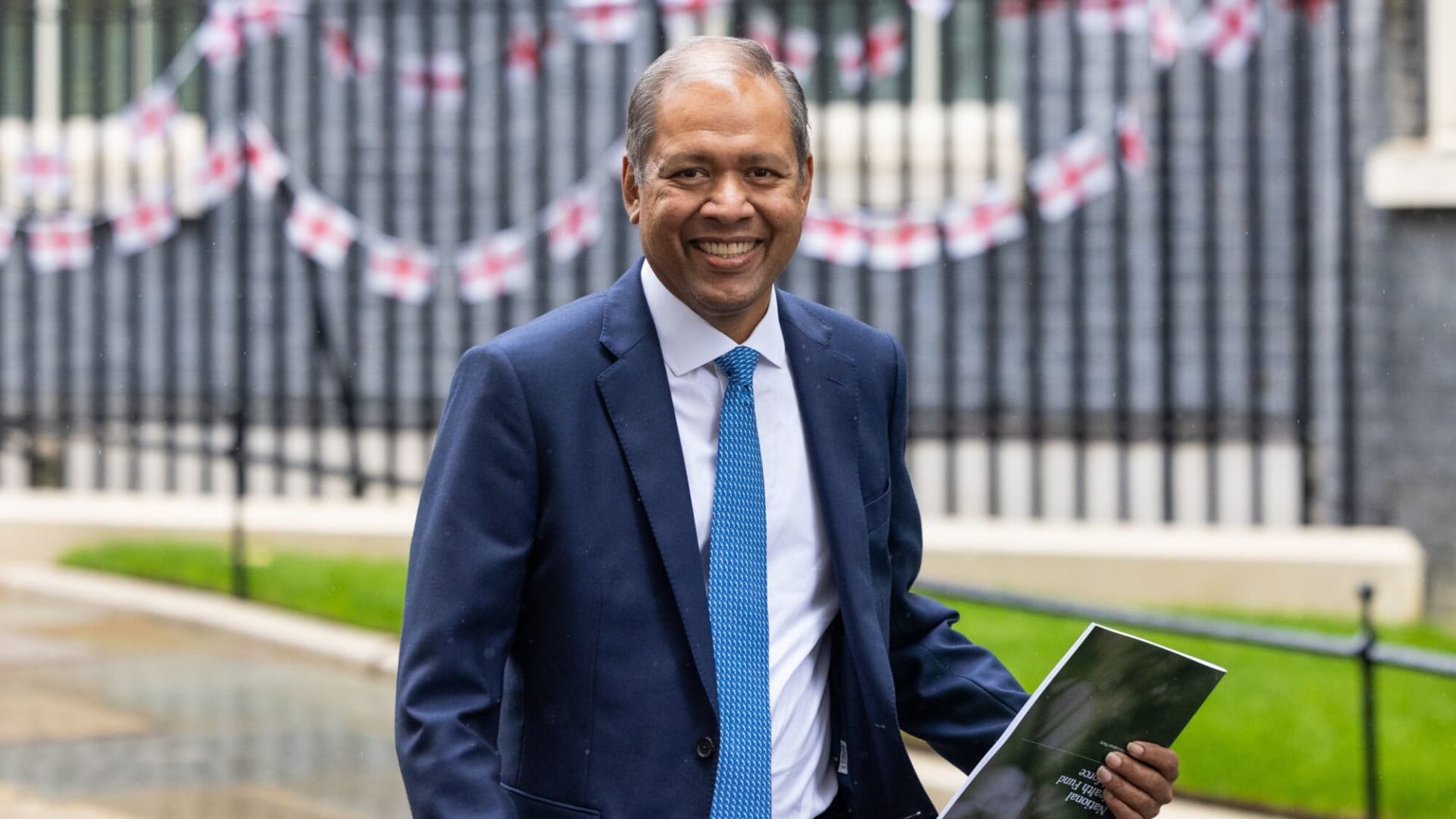

- C.S. Venkatakrishnan said London was already taxing the banking sector more than other major financial centers.

- Despite the criticism, the British bank CEO said the Labour government in the U.K. was a “‘pro-business government”. “I have felt it since the day they walked in,” he added.

Barclays Chief Executive C.S. Venkatakrishnan criticized a proposal to raise taxes on British banks, warning the “facile and fallacious logic” behind such a move would compel the lender to cut back on hiring and reduce lending to the British economy. Venkatakrishnan said that further burdening a sector already facing one of the highest tax rates globally is not a viable solution to the U.K.’s difficult fiscal situation. “If I can use big words, it’s a facile and fallacious logic,” the Barclays chief told CNBC’s Sarah Eisen in a wide-ranging interview Tuesday. “Take the banking sector [in the U.K.], which is already paying a tax rate of 48%, higher than almost any other banking sector.” Contrasting the figure with rates in other major financial hubs, Venkatakrishnan continued, “New York is like 26%, and even the highest in Europe is like 39%, so adding to that is not a path towards economic growth.” In the U.K., banks pay a 3% surcharge on the standard corporate tax rate, which stands at 25%. The Barclays chief executive, however, was referring to a much broader measure known as the “total tax rate,” which aims to capture the entire tax burden that falls on a company as a direct cost, representing a percentage of its commercial profits. The figures were compiled by the consultancy PwC for the trade lobby UK Finance. The U.K. government is reportedly considering raising the bank surcharge by up to 2% in November to help offset part of an estimated £20 billion deficit in its annual budget. London finds itself needing to raise taxes or cut spending drastically after a rise in inflation expectations drove up U.K. bond yields. The U.K. government has also had to reverse its policy on cuts to welfare after political backlash. Robert Woods, chief U.K. economist at Panthen Macroeconomics, said “we estimate that in its forthcoming Budget forecast, the OBR will raise forecast debt-interest costs at the five-year forecast horizon by only [£3 billion]” in a note to clients on September 8. The U.K. Treasury did not immediately respond to CNBC’s request for comment. Pressed on the direct consequences of an increased levy, the Barclays chief laid out a stark scenario. “We would have to find ways to get greater productivity, pull back on hiring, and actually issue less credit into the U.K. economy,” he said. The reason, he explained, is that the bank “wouldn’t have as much capital to reinvest back into the system.” The warning carries significant weight, as Venkatakrishnan noted that the financial services industry accounts for 10% of the U.K. economy and serves as a major source of export earnings for the country. London-listed Barclays shares have risen 40% in 2025, and the lender reported a near-record net profit of about £6 billion ($8.1 billion) in the latest 12-month period ending June 2025, according to FactSet. Barclays also trades in New York. BARC-GB YTD line A ‘pro-business government’ Despite his critique of the specific tax proposal, Venkatakrishnan also expressed broad confidence in the current government’s handling of the economy. He acknowledged that officials have to make difficult choices regarding taxation and spending, but described the administration as supportive of companies. “It is a pro-business government. It is absolutely pro-business. I have felt it since the day they walked in,” he said, adding that the government understands the importance of the financial sector to the nation’s economy. As an alternative to raising taxes on banks, Venkatakrishnan urged the government to focus its spending on long-term investments designed to reverse a national decline in productivity. “That spending has to be investment: investment in housing, investment in infrastructure, investment in long-term productivity,” he said. “And productivity is what’s been declining in the U.K.”